Jane Franklin was born in 1712, in a dirty, smelly colonial city clinging to the edge of the continent. Louis XIV, the Sun King, was still on the throne of France. Daniel Defoe and Jonathan Swift both published books, Peter The Great declared war on the Ottoman Empire, and, in England, John Shore invented the tuning fork.

America was muddling along, skirmishing with Indians and fretting about taxation. But it was 60 years before the famous Tea Party; Boston was content and placid as a colonial backwater.

Jane Franklin did nothing that made history. She did not sew a flag, spy on the British or write even one Federalist paper. Like every woman of her time, she was shut out of politics (and philosophy, medicine, the law, religion, etc.) by social rules that have been immutable for most of human history.

But Jane Franklin was not exactly idle. She cleaned, she cooked, she planted, she butchered, she washed, she chopped, she repaired. She made soap, a two-day process, and sold the extra to make money for the household.

She gave birth to 12 children, most of whom she outlived. Her husband was a wastrel and a fool; she was often close to debtor’s prison and had to take in boarders. Yet she complained little and meditated on Christian theology.

Her story was much like the stories of women everywhere, in the 18th century but also in the 4th century and the 20th century. Men make history and think great thoughts; women do the chores, raise the children, behave piously. Their ideas are not recorded; their triumphs are not commemorated. They are lost to history.

But Jane Franklin was different in one way; she was the beloved younger sister of Benjamin Franklin. She saved his letters to her, all of them. After a while, Ben kept his sister’s letters too, so we have some record of her thoughts, her sorrows, and her preoccupations.

From these and many other sources, Jill Lepore fashioned a biography, “Book of Ages: The Life and Opinions of Jane Franklin,” from which I have lifted most of the data in this post. (All errors mine). The book is an attempt (one of many) to bring the stories of women into the common historical record. It’s a swift and satisfying read, cleverly written and seriously intended.

Jane Franklin loved to read. The books considered suitable for women were mostly dry tracts about moral improvement. Her Boston church was relatively liberal; her brother was even more so. She debated religion with him (he was a newspaperman by training; a skeptic by inclination), and he sent her books filled with new ideas. She read them avidly.

She loved to talk politics; visitors to her house recall being quizzed about the events of the day and asked about the conversations on the street and in the taverns. Which was useful, because the talk on the street was “We’re thinking of starting a new country. Just floating the idea. Thoughts?”

She chided her brother for not answering her questions. but she knew what she knew: Ben approved of independence, and his writings (wry, modest, aphoristic) helped push the country into war.

At the start of the war, the British occupied Boston. There were shortages of almost everything; arrests were common; dying in jail was also common. When winter came, there was little wood for heat. The British eventually decamped, but the war raged on. Families were fractured over political allegiances. Jane hung on somehow; the whole country hung on somehow.

Things got better when the British left. Jane rejoiced in her grandchildren (who seemed a lot saner than her children, many of whom seemed to have inherited their father’s troubled mental state) and traveled to see her relatives in other states. She even went to Philadelphia and lived with Ben for a time.

Finally she had time to read, time to think. She began being bolder in her letters to her brother, arguing (decorously) with the most famous and admired man in America. Their bond remained strong. During Franklin’s tenure as ambassador to France, he gave away samples of the “crown soap” she made as an example of homespun American pluck and ingenuity. So popular was it that he had to keep importuning his sister to send more.

(Franklin was a great manipulator of public opinion. He published a newspaper in which he humble-bragged his way to the top of colonial society. In France, he wore simple clothes and talked in provincial aphorisms, all to reinforce the idea that Americans were a simple people — and thus no threat to France.)

Ben was 81 when the Constitutional Convention happened. He was in pain from a variety of ailments, but he wasn’t about to miss the convention. It was a raucous business, as merchants, farmers, rum-runners, soldiers and other unlikely candidates attempted to make an imaginary country a little less imaginary.

The American Revolution put everything up for discussion. Everything. They knew they didn’t want a king; beyond that, it was open ocean. In the end, they decided voting might be a good idea. Voting!

They also liked freedom of speech quite a bit. That was sorta new.

Jane Franklin was busy writing letters to her brother, urging him to see the world as she saw it, to acknowledge the suffering of war. Here’s a little of what she wrote. I am keeping the original spelling because, as Lepore says, spelling is part of the story. Jane was self-taught; there were gaps in her knowledge, although not in the mind behind it. This is from a letter she wrote as the convention was about to start:

“I hope with the Asistance of Such a Nmber of wise men as you are connected with in the Convention you will Gloriously Accomplish, and put a Stop to the nesesity of Dragooning, & Haltering, they are odious means; I had Rather hear of the Swords being beat into Plow-shares, & the Halters used for Cart Roops, if any of that means we may be brought to live Peaceably with won a nother.”

Peace was not inevitable; the colonies were riven by factionalism. The only way peace could be achieved was by compromise, which depended on reason and good faith. I just want you to consider that for a moment: A political meeting dominated by reason and good faith.

And they got it done. They invented a country. No one was completely happy, but they invented a country.

Benjamin Franklin was the first to speak when the deal was finally done. It was a time of surging nationalism, a time of bunting and conspicuous patriotism. It was a time, in other words, ripe for demagoguery and triumphalism. But here is what Benjamin Franklin said:

“I confess that there are several parts of this constitution which I do not at present approve, but I am not sure I shall ever approve them. For having lived so long, I have experienced many instances of being obliged by better information, or fuller consideration, to change opinions even on important subjects, which I had once thought right, but found to be otherwise.”

So the most influential American of his age announced the beginning of the new nation by reminding his colleagues — by reminding everybody — that human error was inevitable, and that no one person held a monopoly on the truth.

He and Jane both came from humble beginnings. Social rules allowed one to rise while the other remained indentured by custom. She didn’t blame immigrants or criminals or the British. She didn’t even blame men, although she certainly could have. She stayed cheerful; she stayed alive to new ideas. She cherished peace; she loved reason.

I’d vote for her.

Huzzah!

LikeLike

Me, too! But I think Jane knew how to spell a lot of words that, in writing to her brother, she was careless with. Certainly “number” instead of “Nmber”. In New England, girls went to school and learned how to read and write. The Puritans believed that men and women were equal before God, though they also believed that unmarried daughters should act through their fathers, and wives should cede control of business matters to their husbands. All the same, the possibility that a relatively poor woman might have to go into business for herself (as a ‘feme sole’) and that a married woman would be widowed and this, in law, able to control her own affairs was something New England folks thought girls should be prepared for — also, of course, any girl should learn to read her Bible.

The Constitutional Convention members all thought that voting was a good thing. The possibility of having a King was talked about, but never seriously considered. The question was, would people in the states vote *through* their elected representatives, or directly? Madison, with his usual genius, achieved a compromise: Representatives in the House would be directly elected by the voters, Senators, elected by their state’s Legislature, and Presidents would be elected by the People indirectly — they would vote directly for electors, who in turn would assemble and vote for their state’s candidate. Anyone could have foretold that the end result would be a direct election for President on a state by state basis, but no one did, because everyone at the Convention knew George Washington would be the first President and might be elected over and over so long as he was in good health.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had a conversation with my daughter today about the odd dynamic between the roles of men and women, both historically and currently and how, in general, they are pretty sucky. And how wasteful it seems that half the resources of the species are under utilized. And yet; Jane Franklin.

I wrote, many (way many) years ago, a senior thesis to graduate, and it addressed, not the role of women historically, but the historic view of women in history and how that view has changed. A subtle but significant difference. Abigail Adams and Sally Jefferson figured prominenantly. I have added Jane’s new bio to my list and look forward to seeing how we are (in one instance at least) looking at herstory currently.

LikeLike

I’ve always enjoyed Jane Franklin. Thank you for writing about her.

LikeLike

Oh, I am so glad to be taught by you. Good stuff, Jon.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for a wonderful start to 2016. Lovely!

LikeLike

Thanks, Jon!

LikeLike

Wonderful! Oh, I wish I could meet Jane Franklin for breakfast at Saul’s Deli sometime. “Like every woman of her time, she was shut out of politics (and philosophy, medicine, the law, religion, etc.) by social rules that have been immutable for most of human history.” Well, all females were shut out of everything, life included, after dying giving birth one final time. Often before their 15th birthday, more often in their late thirties. Keep these great essays coming — but, I know you will. Grateful.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Love these stories about Jane Franklin, Jon. I’ve got this book on my To Read list. So glad to read your pieces. I always learn or chew on something!

LikeLike

Lovely to read about a new person–to me!–and feel connected, deeply, without regard to time and space, to another human being. Thanks for the trip!

LikeLike

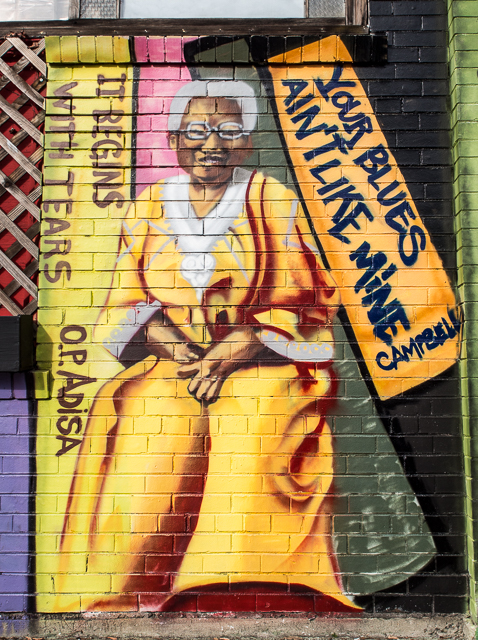

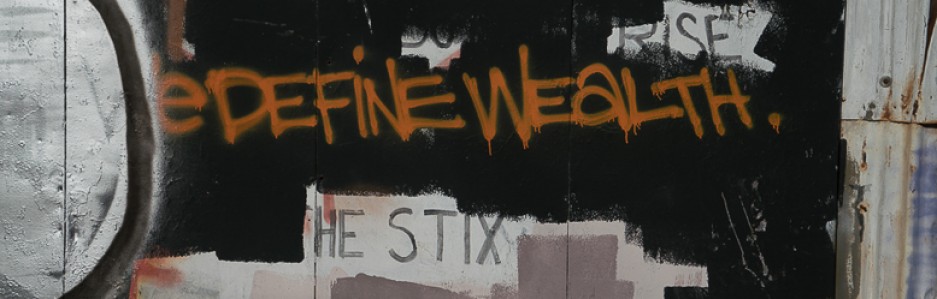

I loved this book. Jon, thanks for bringing Jane to our attention. And Tracy, great photos!

LikeLike

I wonder why at this date & time women , minorities are still dealing with the same issues.Being a woman & a minority & having travelled to countries where the Anglo Saxon male mentality of “I’m King of the Universe”,conquering countries & making the ‘natives’ the inferior race is behind all these attitudes! Look @ who supports Trump!!It’s very worrisome!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Always been that way, I fear. “Why” is a real good question.

LikeLike

Ah, this the Jon Carroll I’ve missed and longed for. Really (a) interesting, and (b) thoughtful, and so much appreciated, please keep it going. Forever.

LikeLike

Aspasia wrote speeches for Pericles during the Golden Age of Greece, but her texts no longer exist. Like Franklin, she moved in a man’s world, but is largely forgotten. Yet, she too was able to give insights to influential men in a time when the world needed the insights of women.

LikeLike

My brain is melting.

LikeLike

Loved this, Jon. Even though “Men [may] make history,” women DO “think great thoughts,” as Jane clearly did. Harumph.

LikeLike

For those of us slogging away at our lives (and enjoying the slog for the most part), I appreciate your posts. It’s obvious you have time to think, and read, and then write–and for that, I am envious but also thankful. I’m going to add this book to my list. Thanks for keepin’ on keepin’ on.

LikeLike

Jon Carroll is back! This is the big guy, warts and all. Thanks!

LikeLike

Nice article, nicely put. One small correction (with implications on interpretation) — I believe your last large quote of Ben is missing one letter, to wit “…but I am not sure I shall Never approve them.” (added “N”).

LikeLike

Thanks David.

LikeLike

Thanks, Jon. Nice to be acquainted with Ms. Jane Franklin.

I’m finding I like having you on my computer monitor, rather than one corner of you sometimes dipping into my cereal bowl as the datebook keeps on sliding off the kitchen counter.

LikeLike

Thank you for reminding me that Jane Franklin existed, Jon. You have a lovely writing style–clear and full of warmth and color. I also want to say that I, too, enjoy the accompanying photographs.

LikeLike